Pacific Bluefin Tuna – Photo credit – NOAA

Last month, the Pacific Fisheries Management Council (PFMC) held its quarterly meeting in Costa Mesa, California. The weeklong meetings are designed to engage fishing industry interests, with participation from commercial and recreational fishermen, fish processors, tribal members, environmental and community representatives, consumers, and the general public. I’ve had the honor of participating in the PFMC process since 2022, when I began serving on the Highly Migratory Species Advisory Subpanel (HMSAS).

The PFMC and its work are creations of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA), enacted in 1976 to protect and manage fisheries within a 200-mile range from the shore called Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The PFMC is one of eight regional councils responsible for managing each fishery through science-based plans that prevent overfishing, rebuild stocks, and promote the long-term health of US fisheries.

Craig Gildersleeve (left), founder of Flying Fish Co. in 1979. Lyf Gldersleeve (right), current President and Owner of Flying Fish Company LLC in Portland, Oregon.

While I joined the HMSAS in 2022, I’ve been involved in one aspect or another of the fishing industry for my entire life. I grew up in a family who owned and operated Flying Fish, a fish market in Sandpoint, Idaho; I spent a year living with a shrimp farming family as a high school foreign exchange student in Ecuador; and I studied aquaculture at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute in Florida. After various early career work, including some in aquaculture, plus sales and marketing, I opened a branch of Flying Fish in 2008. With a humble beginning at Park City, Utah farmers markets and then a relocation to Portland, Oregon, the business grew to a food truck, then a collaborative grocery, to finally its own brick-and-mortar fish market and restaurant, where Flying Fish thrives today.This work has prepared me with experience in seafood, fishing, aquaculture, and sustainability that’s proven beneficial to fisheries policy. I began policy work in earnest 10 years ago, traveling to Washington DC to meet with our elected Senators and Members of Congress and advocate for sound, science-based fisheries management. This work has continued through engagement with elected officials at the local and state levels, public education work through Sustainable Fishmonger programs (and essays like this), and with environmental non-governmental agencies (ENGO’s). Since 2017, I’ve served on the Policy Council of the Marine Fish Conservation Network, a DC-based nonprofit, and I am now in my fourth year on PFMC’s Highly Migratory Species Advisory Subpanel.

Lyf Gildersleeve in Washington D.C. Advocating for sound fisheries policy. (Circa 2015)

At the PFMC meetings last month, I was involved in two topics of current importance: 1.) Marine planning: offshore wind and aquaculture opportunities in California, and 2.) International management of two separate Pacific tuna species.

1. Marine Planning

1A. Marine planning: offshore wind

The advancement of offshore wind has dominated marine planning conversation in recent years. Through offshore wind, Biden administration aimed to create 30 gigawatts of clean energy by 2030, an ambitious plan supported by the Governor of California. However, the accelerated approval process outpaced a thorough assessment of the environmental impact.

These are massive, floating wind turbines, anchored to the seabed thousands of feet deep; electrical cables transmit the energy generated 40+ miles back to shore. In the process, the cables emit electromagnetic waves which have the potential to affect whale communication and navigation, as well as fish migration. Likewise, the blades of the turbines create a danger for migratory birds, with hundreds of thousands already killed by them each year. More over, floating wind turbine technology is largely untested in the US, and given how rough and wild the Pacific Ocean is, we mustn’t rush this new way through without proper diligence.

Windmills in ocean, (not floating windmills) photo credit Unsplash

1B. Marine planning: Aquaculture Opportunity Areas

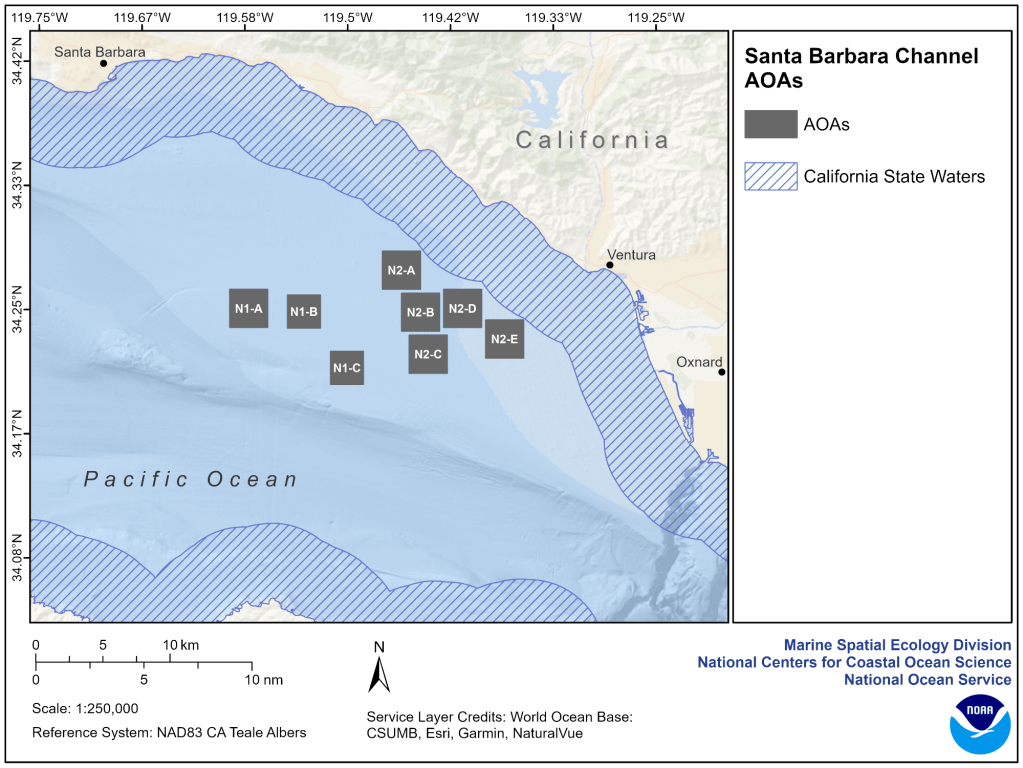

California has likewise identified some aquaculture opportunities in oceanic plots offshore of Santa Barbara and Santa Monica. The current administration issued an Executive Order called “Restoring American Seafood Competitiveness,” specifically calling on the USA to develop an America First Seafood Strategy. The goal is to promote production, marketing, sale, and export of United States fishery and aquaculture products. It also aims to strengthen domestic processing capacity. This places aquaculture as a top priority for advancing the production of seafood domestically.

Aquaculture Opportunity Areas made for a lengthy discussion on the council floor. Many council members have a direct vested interest in the fishing industry; others have indirect involvement with the industry outside of their council roles. Regardless of their position, most of their constituents are sensitive to fin-fish aquaculture — a sensitivity informed by multinational corporations whose operations have decimated the constituents’ marine environments, through changes in scenic landscape and pollution through overfeeding, disease, and waste.

However, an ugly fact that we must face is that over 80% of the seafood consumed in the United States comes from overseas. And of that figure, over 50% is farm-raised — in countries with inferior regulation surrounding water quality, husbandry, processing sanitation, and feed ingredients. To that last point, while American aquaculture practices have improved, we still must find a sustainable feed development that does not rely on the harvest of wild forage fish that wild predatory ocean species rely on.

2.) International management of Pacific Tuna

The meeting schedule for 2026 includes several important meetings focusing on the management of Northern Pacific Bluefin tuna and the Northern Albacore Tuna. Both species are caught in the waters off California, Oregon, and Washington. The coordination of the tuna species is managed by the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), with involvement from the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission (IATTC) as well.

2A. Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis)

Northern Pacific Bluefin Tuna

Pacific Bluefin tuna: Photo credit: Adobe Stock

As recently as 10 years ago, bluefin tuna was classified as overfished. But with a 20-year rebuilding plan, the halfway point contains some good news: with still 10 years left on the plan, the stock has already hit its benchmark of 20% of historical biomass. These management measures, largely built around total allowable catch of the species, were built on international collaborative strategy with input from the United States, South Korea, Japan, and Mexico, to name a few.

However, managing stocks with vast differences in culture, language, regions, and sociolocal norms is challenging, as one might expect. Collectively, the group assesses and analyzes fishing-based data including the volume of catch reported and how many days the boats fished to determine models. The models then calculate the total biomass of that species of tuna in the ocean. Then, parameters are set for the total allowable catch (TAC), a percentage of the total biomass, and the TAC is divided between the countries who share the resource. This is where things can get heated and negotiation is paramount. No one wants to reduce their revenue, but ultimately fishermen want what’s best for the ocean, a necessary recognition toward continuing their lifestyle and way of life on the ocean.

To this end, the 2026 meetings are of highest importance, with the highest of stakes on how we manage the stocks as they build and repair. At the PFMC meetings in November in California, the council recognized the importance of US stakeholders and fishermen participating — a major negotiation position when it comes to allocation and rebuilding benchmarks. For more information on International management of tuna in the Pacific Ocean check out IATTC and WCPFC.

2B. North Pacific albacore tuna (Thunnus alalunga)

Pic: Northern Albacore (Oregon Albacore Tuna). Photo credit Oregon Albacore Tuna Commission

The North Pacific albacore tuna is the one we catch off the Oregon & Washington coast in the summer. They used to be more prolific off the California coast, but over the last 20 years, the stock has been moving north, leaving California’s albacore population low. It’s another example of how climate change is affecting the oceans, currents and migratory paths of fish. These fish follow the exact water temperature that makes them feel comfortable. They also seek the water that holds the food they are after. If the water current, food sources, and location change, then the tuna change with them.

Currently the North Pacific Albacore population is abundant, with no overfishing taking place. In fact, this year (2025) was the best year in a decade for Pacific fishermen catching albacore. This points to success in the overreaching harvest strategy to manage the stocks so that they don’t drop below historic levels. This strategy includes measures to reduce fishing pressure if the stock drops below total biomass thresholds. Yet, at the moment there are no explicit reduction measures or rebuilding structures in place.

If and when that time comes, American fishermen need to have a plan to reduce pressure on the stocks. One method is limiting the total number of boats fishing for albacore. Another is reducing the total amount of days each boat can fish on the water. Also, the total weight of fish each boat catches can also be reduced. Other techniques can help reduce pressure on the stocks too, each with its own benefits and weaknesses. All of these options will be reviewed in the 2026 meetings; stay tuned for more info.

As you can tell there is a lot to discuss, and lots of opinions about each of the topics. I am proud to apply my background and experience to this work, and I enjoy doing it. I likewise always look forward to educating as many people as possible and welcome all to get involved in the process. Thank you for reading and caring about our precious resources in the Pacific Ocean and beyond, and stay tuned for more. Please don’t hesitate to reach out directly to me for more ways to get involved- oregonfreshfish@gmail.com

Lyf, Albacore fishing off Oregon Coast

Until next time,

Lyf Gildersleeve- Owner of Flying Fish Company LLC- Portland, Oregon & Sustainable Fishmonger 501(c)(3) non-profit.

Leave a comment